Improvised homes lining a hillside, stacked one on top of another… It’s a common sight in Latin America – cities built by the Spanish in mountain valleys eventually run out of space as they grow outwards, so they creep up hillsides in informal settlements full of tiny homes with million-dollar views, impoverished residents and almost no basic services.

These slums are called barrios in Spanish, a term which covers all versions of informal settlements – flat or inclined, well established or just forming.

Most municipal governments have a mixed policy toward city barrios combining political indifference with law enforcement aggression. Yet in mid-July 2019, mayors from 70 big cities around the world were touring one such barrio in Medellin, Colombia called Comuna 13. Foreign mayors joined by press crews and sweating secret service agents rode shiny electric escalators up the hillside barrio of Comuna 13 and were greeted by clowns and residents.

One month earlier I was taking that same surreal ride on the world-famous escalators that have transformed Comuna 13. With my bilingual Medellin guide John, we traveled upwards into the very heart of the barrio. The ride into Comuna 13 also transformed my guide. John instinctively switched to inner-city swagger mode; suddenly he was speaking barrio Spanish and doing elaborate handshakes with nearly every local we passed. It was their turf and John morphed to fit in.

Many foreigners who have never been to a Latin American barrio might be intimidated entering such an area. It’s easy to feel out of place, and not from mere paranoia either. These informal neighborhoods are often dominated by gangs who fill power voids left by deficient or overly aggressive government practices.

But for this 2019 version of the notorious Comuna 13 of Medellin, John and I, like the smiling world mayors, were on a “loving the barrio life” tour. In the higher reaches of the Comuna we encountered other foreigners, backpackers took selfies in front of massive graffiti murals, music played, food and tee-shirts were sold, NGO types held sack races for barrio children... Cynics would call it poverty tourism. Optimists point to Comuna 13 as a miracle of progressive politics. It was not always that way…

Once a war zone, the Comuna 13 is not your average South American barrio with a distinguished gang resume. In the late 1990s it was considered one of the three most violent places on the planet. Rising up a steep hillside on the outer limits of city district 13 of Medellin, Comuna 13 was a refuge for people fleeing armed violence in the Colombian countryside in the 1970s and ‘80s.

Barrio 13 residents had become the obligatory subjects of armed groups, during the very time that those armed groups transformed themselves from Marxist rebels to drug lords. The rebels-turned-cartels controlled the Comuna 13 by intimidation, but also by patronage, giving loyal residents some benefits. Like any mafia, they took care of those loyal to them. These groups looked after 13 as a strategic zone in western Medellin for the movement of weapons and drugs.

In 2002 the mayor of Medellin, with support from Colombia’s president, decided to take control of Comuna 13 by force. Operation Orion it was called, and it was a horrific event for Comuna 13. An unholy alliance of police, army and crime lords stormed he barrio, causing numerous deaths and widespread destruction. In the wake of Operation Orion, paramilitaries ruled the barrio, by many accounts with even more brutality than the rebel-named drug gangs and without the perks. Human rights abuses were common and sometimes fatal, and perhaps worse, other armed groups and gangs continued to operate. Then everything changed…

One of the biggest causes of unemployment and violence within the barrio was its isolation from Medellin. Partly this was due to the lack of a positive government presence, but even more importantly, there was no infrastructure that integrated Barrio 13 with the rest of the city. With no roads and just a few endless sets of concrete stairs, it could take nearly an hour for residents to return home to the barrio. This slow steep trek meant passing through gang-controlled areas and made getting to work and back an odyssey or worse.

On May 6, 2012 the government inaugurated a half-million (U.S.) dollar outdoor escalator project that whisks residents up the hill in six minutes. Other community improvements have followed, but what caught everyone’s attention was these shiny electric escalators in a hillside barrio with homes stacked one on top of each other. The visual impact took it beyond a social benefit. It was so surreal, funky and new it became an overnight success with tourists from around the world.

It was an interesting place to walk around. The views of Medellin are amazing and the residents exuberant, seemingly in permanent festive mode. There is a great deal of energy in the youth of the Comuna 13 and you can still sense that some people are at a loss with what to do with all the youthful exuberance. Walkways that traverse the barrio are filled with kids and venders.

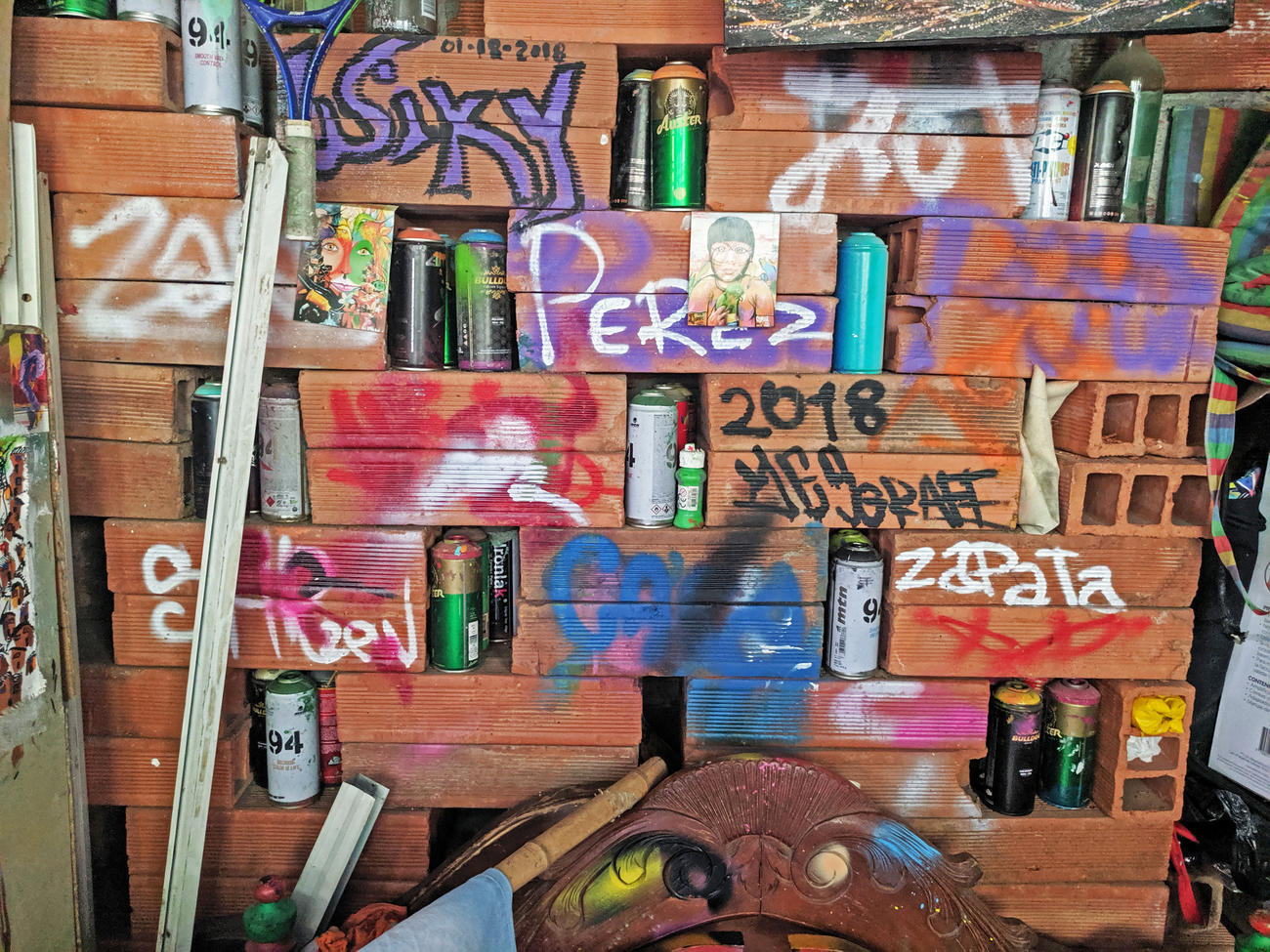

The escalators themselves, the improbable centerpiece, are spotless, shining machines that work in stark contrast to cinder block homes with crumbling zinc roofs held down in the wind by stones and debris. Graffiti murals are giant and bold, with a rough visual edge – hummingbirds look like bikers with studded armor, shocked expressions of fear are common, and the colors are beyond intense. It is angst-driven art, beautiful and authentic, but unsettling.

After a walk around the upper reaches of the barrio, I sat down with my guide John in a café he founded with one of the most prominent Comuna graffiti artists known simply as Chota 13. The business is called Café Aroma de Barrio, a super hip hangout that received a steady flow of foreign backpackers during my stay and even had photos of ex-president Bill Clinton enjoying Aroma de Barrio’s ambience plastered all over one of its walls. Aroma de Barrio also serves beer, and many young patrons were enjoying a cold one watching people ride the escalators or staring out at the endless view of Medellin.

Aroma de Barrio was the cool place to be, but graffiti artist Chota 13 was not in that day. Lucky for me my hot chocolate was shared with my guide and co-owner John, and he showed me around Chota 13’s studio inside. It was a small space, but so awash with color and funky props it was hard not to be impressed. The place reeked of creativity, the footprint of making masterpieces out of hardship.

It all seemed to good to be true. The journalist in me could not buy it all. I asked my guide John what happened at night? Was the barrio really as safe and rosy as it looked during the day? He shrugged sadly. Comuna 13 remains a work in progress.

Business owners like John and Chota 13 pay a protection fee to the controlling youth gang and yet another protection tax to local police. Plans for a second floor for the Café Aroma de Barrio have been blocked by the local government, in an area where urban zoning is both impossible and unheard of, construction has been stopped, apparently due to a lack of bribes.

For some elements in the barrio, the past is hard to let go of. That said, the future for Comuna 13 looks bright. In Medellin and this remarkable hillside neighborhood, 13 can now be considered a lucky number.