Behind The Veil: Reflections on Iran

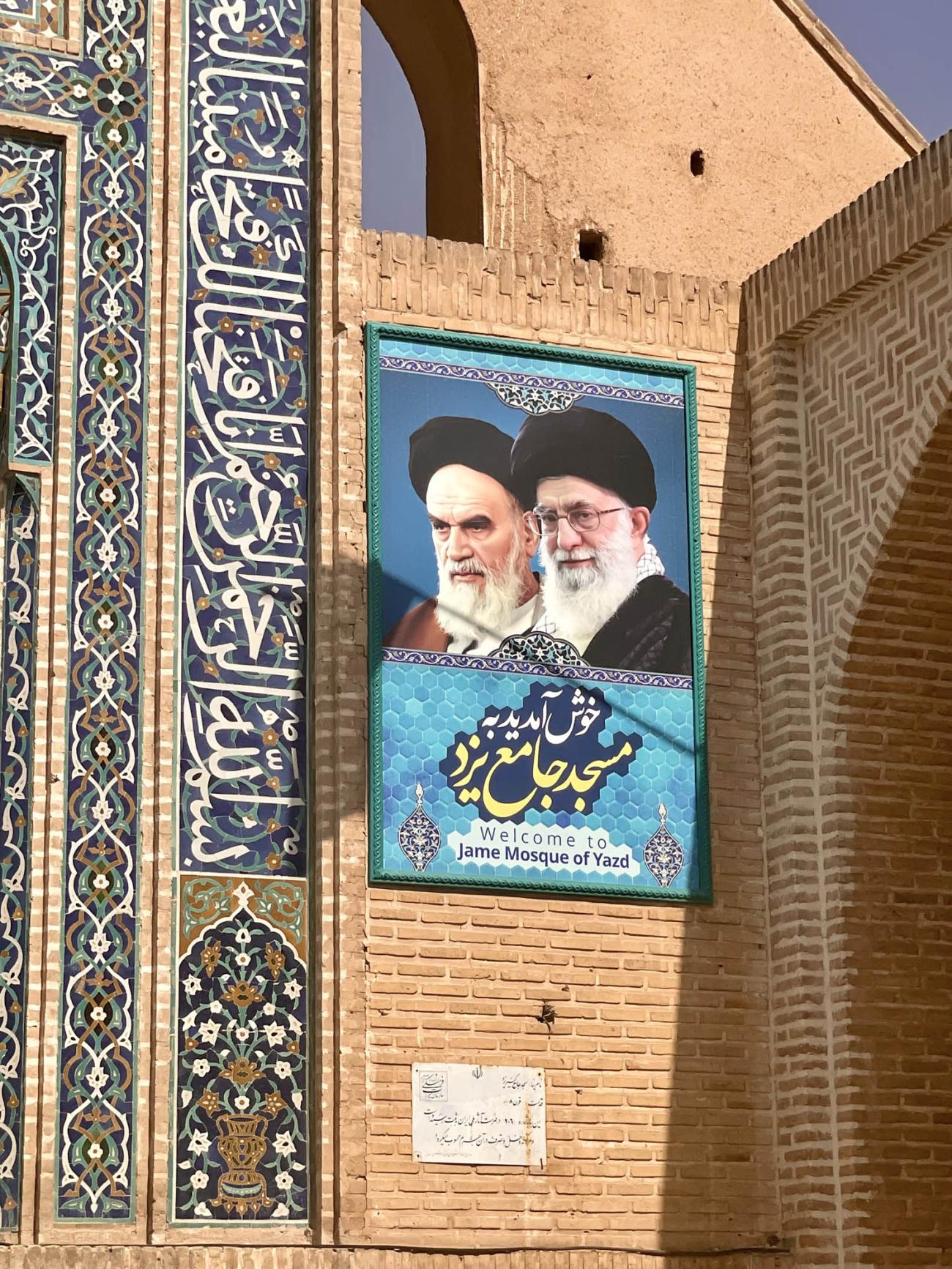

Outside Tehran’s Airport, the sky over Iran is bleached white with heat, and five or six scrawny goats shelter under a grey tree. Dust and litter devils swirl along the sides of the road as we take the airport highway into town. A massive Iranian flag stands to stiff attention in the wind, the Ayatollahs Khomeni and Khameni glare down from a giant poster on the high walls and black pocket handkerchiefs on long strings flap over the entrance to a cemetery.

My long-held dream of going to Persia, inspired by Rumi the poet, Sabrina Gayour’s Persiana cookbooks, tales of The Silk Road, a love of mosaic, and a desire to leave the well-worn travel path is not mirrored in this scene. Maybe the 98% of people who questioned my embarking on this trip, “Is it safe?”, “Those are dreadful people,” “What for?” were right – what on earth am I doing here?

“Are you travelling alone? Do you have a husband? Where are you from?”

Under the inky night sky, my new friends Babak and Edi warm to their questions as we walk along the pathway back to our rooms after dinner in our desert eco-lodge. They are on vacation, 500km away from their home on the Caspian Sea. It is Edi’s first time to experience the desert. Babak, a Persian Literature major from Tehran University is confident and charming: the spokesperson. Edi, doing her Master’s degree in mathematics, is the curious one, posing the questions.

“I am with a tour group: there are eight of us, two from the US, three from England, one from Singapore, one from Ireland, and me.”

“My husband is at home.”

Too much information to share that Iran is dry, and the thought of a two-week holiday without beer was unattractive to him.

“South African, how can you be?” Babak asks, as she lightly touches the inside of her wrist.

“Well, my family have been there for 150 years.”

“And before that?”

“England.”

“Ah, okay.”

Viewed from the perspective of the people of Persia who have been here for 6000 years, my South African heritage feels questioned and questionable. This is why we travel.

A week into the tour, it is the anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s death. A Kurdish activist, she was arrested for not wearing her hijab properly and died in the custody of the morality police in September 2022. Her death sparked riots across Iran which took months to quell. As a pre-emptive action, the authorities have closed almost everything, including the sights on our itinerary for the weekend. Our guide is reeling, juggling uncertainty, expectations, and promises. I pass on the proposed alternative, a day trip to a waterfall, and declare a half-time break.

Relishing my freedom (British and American tourists must be accompanied by a guide at all times in Iran), I head out onto the deserted streets of Shiraz, the city of poets and nightingales. I linger over a cold brew coffee, drift through an independent bookshop, specialising in poetry, and land up on the main street, looking for lunch – for the first time as our tour is fully catered. The smell of lamb kebab cooking over an open gas flame lures me into a well-patronised brightly lit cafeteria establishment, and I am shown to a table at the back.

The menu in Farsi is unintelligible but there are pictures, and I point out my choices to the busy black-clad Mama who is running the show. Dad sits at the entrance and mans the till. With my fork and spoon, I relish my lamb with the obligatory rice, tomatoes, cucumbers pickles, and yoghurt on the side, and take the opportunity to observe my fellow diners, out and about on this declared public holiday. The sole woman patron in the place, I am slightly self-conscious of my headscarf which keeps slipping off. Three men in military uniform share a huge platter of food next to me, eating ever so neatly with their fingers, balling up the rice, dipping it in the sauces and popping it into their mouths.

Everyone seems to order and pay at the front before sitting down for their meal: I have been afforded tourist privileges. I approach the till somewhat hesitantly making paying motions with my hand and receive a printed till slip with Farsi writing and numbers. Opening my purse, I offer it to Dad who extracts the correct amount and I cruise back out onto the baking hot street, relishing my role as an independent sixty-year-old solo woman traveller in Shiraz. Until I get back to my hotel room and look at the till slip: across the top is written, “Ms Marpel”.

Wikipedia tells me I have been labelled as Agatha Christie’s elderly spinster amateur detective!

The women of Iran are beautiful, with golden skin, lush dark hair and eyes ranging from hazel to walnut brown. While I battle to keep my head and ears covered, and resort to a hat and a cotton scarf tied around my neck, they wear their hijabs with panache and style, an oval frame, offsetting their beauty. I am fascinated by how far back some manage to wear their scarves, showing off their hair to best advantage. And then there are many, particularly the younger women, who just refuse to wear it.

“Why do you as a foreigner wear hijab?” Marzieh, a thirty-something yoga and music therapy teacher in Shiraz, asks me as we chat on the street.

I stutter in response, “To acknowledge your culture and the laws of your country.”

She continues, “We, the women of Iran are protesting. We want our freedom. We do not want to wear this hot, limiting thing, and we are fighting against this and all the other restrictions against women. We are a nation of 85 million Iranians, ruled by 200,000 mullahs. We will keep on protesting until things change.”

The spunkiness of the women is striking as is the feeling of sisterhood and courage. “Woman, life, freedom”, the slogan of the Mahsa Amini uprising, is reflected in the five young girls we meet at a riverside picnic: dressed in black with kohl eyes and bright faces, not a headscarf in sight, they are confident, questioning, alert and alive with questions for all of us in the group.

The highly dismissive way in which they talk to a black turbaned mullah (holy man) walking by, “Get out of the picture. You are not welcome here.” is remarkable and strikes our guide as extraordinarily outspoken.

“Ah, South Africa. I was in Cape Town once in 1999. Come and drink tea with me.”

Iraj, the proprietor of a carpet shop in the Esfahan bazaar, invites me into his shop. Seated on the couch, we talk of his upcoming saffron harvest, prices and sanctions, the beauty and abundance of handcraft in Iran, and carpets.

Iraj owns land out of town where he cultivates the crocus flower, the stamens of which are dried to produce saffron. He reverently lifts a tin out of a dark concealed bench, and with pincer precision, extracts two strands of the crimson threads and drops them into my tea. The tin smells of fresh hay, clean earth and a hint of honey as he passes it under my nose.

In mid-October, he will return home for the annual harvest. At six in the morning and six in the evening, for an hour at a time, over the course of twenty days, the purple flowers will be hand-picked in the fields. The stamens are then painstakingly removed from each flower and dried on a mat. The yield from his lands will be about 1.5 kg of this precious golden spice. No wonder it is so expensive.

Ninety minutes later, I leave the carpet shop with the gift of a small tin of saffron, and a small brown package, the size of a five-hundred-page paperback book. It conceals a double-sided silk nomad carpet, my treasure of Iran. But even more precious than the silken feel of it under my feet as I get in and out of bed each day, is the memory of the absolute trust and mutual respect which accompanied this interaction.

The economic sanctions imposed on Iran include its exclusion from the SWIFT banking system. As a foreigner, it is impossible to draw money from an ATM or use a credit card for purchases. Iranians use cards all the time – cash is the second choice, and change can sometimes be an issue. Consequently, I am limited in my spending to the US$500 cash which I’ve brought with me.

Until I fall in love with my carpet.

“Just pay a deposit,” Iraj says, “and you can send me the balance when you get home.”

“You don’t understand, Iraj, I have only $20 to last me the next four days until I leave Iran.”

“Well then, take the carpet, and you can pay me when you can access your internet banking.” We have shared a cup of saffron tea, and now this man is offering for me to walk out of his shop with my carpet and a promise to pay.

The trust flows both ways. Within minutes, I am onto the shop’s Wi-Fi network and VPN, credit card and passport details are winging their way to a contact in Dubai, Arab Emirate Dirhams are disappearing from my account, and I am the delighted owner of a fully paid-for silk beauty.

The adrenalin surging through my system precludes sleep that night, and it takes a while for my inner auditor to come to terms with what I have done. I also have to tip my hat to my husband sitting on the veranda in Johannesburg, dealing with his frenzied carpet-obsessed wife asking for his credit card and passport details to make up the purchase price within the banking limits on our cards. I would not have been as accommodating.

Early the next morning, I meet Negin and Nahid on the street. Nahid is starting a new job that morning. She has a Master’s degree in English translation and has worked as an English tutor at a private college for several years. Her new job is in telesales for a water purification systems manufacturer. She is excited. I share with them my joyful carpet story, and Negin offers to buy me a cappuccino.

Farsi is a softly spoken language and during my two-week trip, I have only heard one raised voice: a woman’s. Early one morning outside my hotel window, she was on her phone, and it sounded like a frustrated mother trying to get her children up and moving.

The people of Iran are both proud and gentle. Self-deprecating in the extreme, our guide frequently refers to lazy Iranians and bad Muslims and reflects on the four million Afghan refugees in the country:

“They are happy because they’re safe and employed, we are happy because they do the jobs we don’t want to do for a cheaper price.”

He also relishes listing the numerous things that Persia has given to the world, including shoelaces, algebra and geometry, the federal system, credit cards, carpets, pointed arches, wind towers, polo, backgammon, and ballet dancing en pointe. And is very proud of the fact that the Persians never had slaves. Servants yes, but slaves never.

Respect and honour, grace and propriety are values which underpin Iranian culture. Ta’arof epitomises this. It is a way of showing respect by saying something you don’t necessarily mean. Our guide summarises it as an Iranian etiquette idiosyncrasy whereby it is appropriate to say ‘no’ for the first, second and even third time to something, even if you really want it. It has been known to cause some confusion when a taxi driver answers to the request for the fare, ‘please don’t bother, it was nothing’, and the foreigner takes him at his word.

So, in response to Negin’s offer, I politely decline, once, twice, and as I’m dithering whether now is the time for the affirmative yes, she dissolves into laughter and says, “Are you practising ta’arof?” The cappuccino is delicious.

Before she leaves for work, Nahid and I talk about picnics. Everywhere I have been, multi-generational families are seated on their Persian carpets, enjoying picnics. Hot water thermoses filled with tea, tins of biscuits, tomatoes, cucumber, white cheese and flatbreads, gas cookers in car boots, or small charcoal fires and blackened kettles, it isn’t about the food and drink, but rather the sense of community and shared joy in the outdoors which is striking.

Fathers proudly carry their children in their arms, not a pram in sight, and tiny babies are out in the searing sun, sometimes being surreptitiously breastfed. And no one wears a hat. Nahid shares that just last night, ahead of her younger siblings returning to school after the summer holidays, she and her family, twenty-five of them, picnicked in the nearby Naqsh-e Jahan Square. The cool evening air, the dancing fountains, saffron and pistachio ice cream, magnificently lit mosques and palace: a run-of-the-mill evening in Esfahan. No finer place to make family memories.

And for me?

My memories of Iran include the scent of saffron, rosewater, cardamom, cumin and cinnamon. The taste of pistachio gaz (nougat), crumbly chickpea flour biscuits and hearty vegetable soup. The abundance of aubergines and tomatoes, walnuts and pomegranate molasses, lime juice and halva. The magnificence of the handcraft, both ancient and modern, including mosaic, stucco, miniature painting, embroidery, metalwork, and of course, carpets.

But ultimately, my memory of Iran is of the people.

So far removed from the foreboding posters and black flags of my arrival, it is of their warmth and energy, hospitality and grace. Our shared humanity. And the open-hearted welcome they afforded me.